Why can’t we build anything? (Part 2)

One of the major themes we are working on these days at the Extra Crunch Daily is trying to understand why America and many other Western nations can’t seem to build infrastructure anymore. The answers are complicated but critical: our infrastructure is decrepit, climate change is intensifying, and population growth will put even more strain on existing facilities.

In our first part in this series, we wrote about a book entitled Politics across the Hudson, which was written by Phil Plotch. He formerly headed the redevelopment of the World Trade Center following 9/11 and is now a professor finishing up a book on the travails of the Second Avenue subway slated for publication later this year.

We interviewed Plotch this week to get more details on what causes delays and cost overruns in infrastructure, and these are some of the most interesting highlights of our conversation:

- Misinformation is a huge challenge at all levels of infrastructure planning. “People at the bottom don’t understand what is happening at the top, and the people at the top don’t understand what is happening at the bottom,” Plotch said. A cost increase that might be relatively cheap to handle immediately won’t be reported since it might piss off politicians whose support is critical for a project.

- That type of purposeful misinformation is a huge problem at the Federal Transit Administration, which administers funds for mass transit across the country. Many of the funds are competitive, and “when there is competition, there is a lot more … gamesmanship,” Plotch said. Cities will overstate benefits and understate costs in the hope of winning funding from the federal government. “The FTA figured this out and Congress figured this out so they put in this whole bureaucracy to review the benefits,” he said. “They are trying to do the right thing … but it just slows down the process.”

- Plotch uses a term called “vaportrain” (the locomotive version of vaporware) to describe many American infrastructure projects. Politicians want to demonstrate their bold and entrepreneurial risk-taking on infrastructure, but are daunted by the time and expense required. So they study things. Regarding the Tappan Zee bridge replacement, which is the focus of his book, Plotch wanted to ask “why was the state studying the same thing over and over again? … It wasn’t until I talked to three governors that I realized what was going on.” The issue was that a train over the bridge was widely popular but expensive, so it “just got studied year after year … it was easier to study something than actually cancelling it.”

- Another challenge is scope creep, which should be familiar to any software engineer. While working at the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, Plotch worked to draft a plan to connect a train from lower Manhattan to JFK Airport in Queens. When he reached out to a Congressman in Queens for federal sponsorship, “he came back and said he wanted 5%.” What he meant was “5% to be invested into his community in some shape.” Plotch analogized it as “they see it like a Christmas tree with a whole bunch of ornaments on it, and they want to add their ornaments to it as well.”

- A better model for infrastructure today is to focus on minimal operable segments. The idea is that, instead of planning an entire route such as California’s SF to LA high-speed rail line, try to identify more limited routes that can be built efficiently and get to operation as quickly as possible. It’s the equivalent of an MVP in startuplandia, except that the MVP here often costs billions of dollars.

- Wicked problems are policy challenges that are “difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognize” in the Wikipedia definition. In infrastructure, Plotch said that wicked problems are often just problems of realistically assessing what is possible given constraints. When it came to the Second Avenue subway, “by overpromising they tied themselves up” for years, and with no progress to show for it.

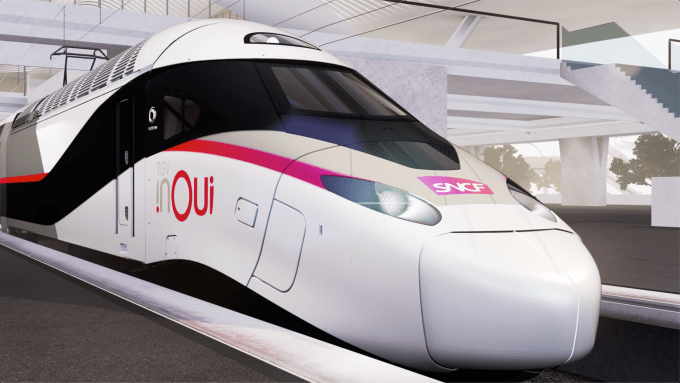

France’s new high speed rail trains will do everything but cure cancer

Video still courtesy of Alstom

Written by Arman Tabatabai

Continuing discussions on infrastructure, French national rail operator SNCF launched its new high-speed train that it will be rolling out through 2023. The new model will be faster, more spacious, consume 20% less energy, and perhaps most importantly, will cost 20% less than the SNCF’s current model. In addition to being more profitable and efficient from a ridership perspective, the new model offers up a cost-efficient solution to actually save money while reducing emissions as the climate change fight seems to grow more dire daily. The launch is the latest in France’s broader expansion of its high-speed rail network and shores up the national rail operator’s economics before the country begins allowing companies to provide competing service in 2021.

India’s overlooked SaaS startups

Image by jayk7 via Getty Images

Written by Arman Tabatabai

Earlier this week, Extra Crunch spoke with The Billionaire Raj author James Crabtree about the hurdles India has to overcome in order to reach the same magnitude of tech relevance as China or the US. The discussion called our attention back to a feature in the Times of India last month focused on the rapidly growing SaaS ecosystem in Chennai and greater India. The piece explains how the strength of India’s SaaS startups often gets overlooked in favor of the country’s more brand name consumer unicorns, despite raking in massive revenues and rapidly gaining share in the global SaaS market.

Chennai alone is home to multiple billion dollar companies including Freshworks and Zoho and has brought in more than half a billion in venture capital. One of the main takeaways of the piece was that much of the sector’s growth can be attributed to the city’s growing talent pool which in part flows out of its comprehensive university system and engineering think tanks.

Yet talent has also now become one of the largest limitations to the growth of the ecosystem, as India struggles to bring in foreign expertise to help propel it through its next phase of expansion:

“If only we could also make it attractive for global talent from anywhere in the world to work in Chennai or elsewhere [in India], a lot of challenges can be solved better,” says Chargebee’s [Krish] Subramanian.

India’s SaaS sector is an interesting candidate for examination. On a global level, the ecosystem is yet another example of how talent can make or a break a country’s entrepreneurial future, as we’ve discussed several times in regards to immigration. On a national level, India’s SaaS community seems to mimic a broader dynamic in India’s tech industry, where critical structural impediments stand in the country’s path to becoming a dominant innovation economy.

India’s founders are losing trust in VCs?

Alessandro Di Ciommo/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Written by Arman Tabatabai

Indian financial publication Mint published a detailed walkthrough of the country’s long history of rocky founder-investor relationships. The story explains how the shaky track record has led to a fundamental distrust between new Indian entrepreneurs and VCs, as founders have become increasingly skeptical, combative, and demanding of venture capitalists.

The piece frames the trend largely through Indian rideshare giant Ola’s ongoing tussle with SoftBank, following public reports about Ola’s determination to avoid additional SoftBank’s money.

Investor battles in India’s tech scene seem poised to only become more frequent. Having now seen billion dollar companies, exits, and success stories, India’s more knowledgable and experienced entrepreneurial community no longer views venture capital as a blessing and feels it has the leverage to demand better terms and more control.

And as founders and alumni from the many successful Indian companies that have had less than peachy investor relationships — such as Flipkart, Snapdeal or Ola — reinvest time, money and knowledge back into the ecosystem, the negative bias towards investors has the potential to get recycled through the entrepreneur community.

There is a clear lack of trust between India’s startup and venture communities, which ultimately threatens the sustainability and growth outlook of the country’s tech sector.

But a solution to the problem is not so cut and dry. Mega growth funds like SoftBank and Tiger Global have given limited control to their Indian portfolio companies and have forced their hands on numerous occasions. Yet Ola’s avoidance of SoftBank has led to lower valuations and more difficult and lengthier fundraising processes.

According to Mint, other potential investors have even shied away from writing checks due to the sheer fact that there’s no chance for a future SoftBank mark-up or cash injection. As more and more companies surpass the billion dollar valuation mark, the avenues for capital become more limited, which often means terms are pushed in favor of investors. Ola is taking a hard stance for control over capital but it’s unclear what impact that will have if and when it no longer has the luxury to do so. In either case, the tradeoffs that come with megafund capital is something more and more growth stage companies will have to consider if they want to follow the trend of staying private for longer.

Obsessions

- We have a bit of a theme around emerging markets, macroeconomics, and the next set of users to join the internet.

- More discussion of megaprojects, infrastructure, and “why can’t we build things”

Thanks

To every member of Extra Crunch: thank you. You allow us to get off the ad-laden media churn conveyor belt and spend quality time on amazing ideas, people, and companies. If I can ever be of assistance, hit reply, or send an email to danny@techcrunch.com.

This newsletter is written with the assistance of Arman Tabatabai from New York

from TechCrunch https://ift.tt/2Tma2Pz

via IFTTT

Comments

Post a Comment